by Defne Caldwell, High School Teacher

You may or may not have read a little book with a compelling title, Why Read Moby Dick?, by Nathaniel Philbrick. In it, Philbrick explores elements that are significant to Herman Melville’s novel, such as the disastrous tale of The Essex, a ship sunk by a sperm whale in 1820 which inspired some aspects of Melville’s tale (and Ron Howard’s film). Philbrick’s book also includes several essays on themes, characters and scenes within the novel, and a wonderful chapter on chowder. Margaret Atwood wrote a column in the “New York Times” several years ago about what she would tell Martians wishing to understand America. Among other things, she tells them to read Moby Dick. Their response, “Holy crap! Does this mean what we think it means?” They understand the novel as a metaphor for North America’s 21st century role in the oil industry. In October, I will be teaching Moby Dick to the tenth graders in “The Novel” main lesson, so I too am thinking about why we read Moby Dick, and what a fifteen or sixteen year old has to gain by it.

“Melville’s novel is rich in symbols uniquely meaningful to young readers.”

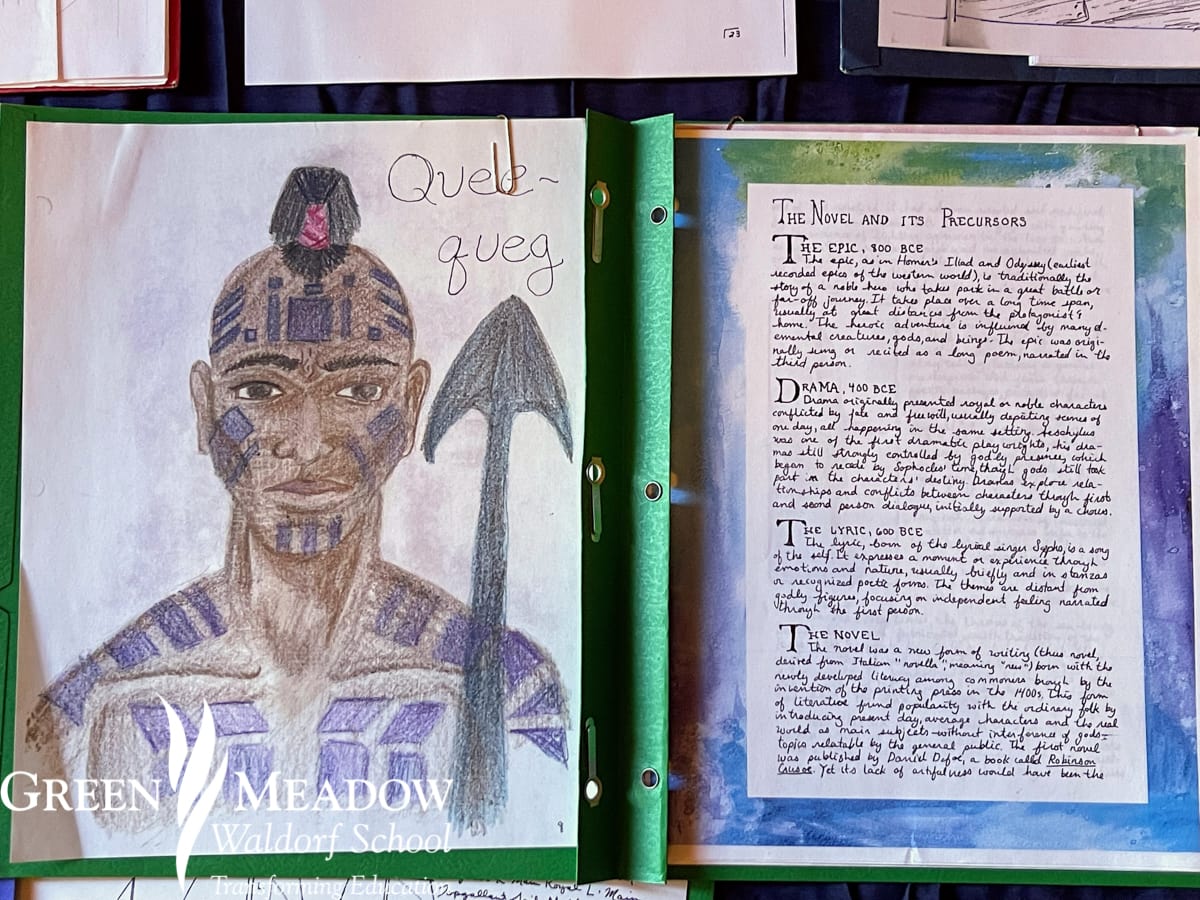

In some ways the novel, a form of literature that followed epic, lyric, and dramatic literature by around 2,500 years, is a more contemporary art form. In the adolescent’s appreciation for what is real, what is present and now, this form of literature meets them where they are. Moby Dick has within it passages that are decidedly epic, lyric and dramatic, and in this way it encompasses all literature that has come before, but is revolutionary and new in the way that it takes them up. This is also the experience of teenagers who are picking, choosing and recombining what they inherited in order to make themselves their own person. The theme of independence runs through Melville’s novel, which speaks strongly to the students who are close enough to home and school to notice the sharp contrast of moments of independence. And the young person’s desire to travel far from home is matched by Ishmael’s need to escape the weighty experience of land and go to sea. The novel also meets the adolescent’s experience of strong, dizzying waves of sympathy and antipathy. Moby Dick too is rich in polarities, Ahab’s selfishness and pride vs. Pip’s selflessness and shame, Ahab’s passionate monomania vs. Ishmael’s thoughtful open-mindedness, lulls vs. storms, descriptive passages vs. dramatic passages, the list goes on and on. In considering ideas in relation to eachother, the adolescent’s thinking and feeling has freedom to move and to come into balance.

Melville’s novel is rich in symbols uniquely meaningful to young readers. The gold doubloon, promised to whoever spots Moby Dick, is regarded by many characters on the ship. Each view of the coin is in a way true, yet the truth lies somewhere in the combination of all points of view. This meets the students who have an increasing appreciation for varied points of view, yet an increased interest in truth. Ishmael studies a loom on the ship used for weaving mats. Always on the lookout for meaning, Ishmael muses that the fixed parts of the loom represent necessity and fate while the moving shuttle must be free will, Queequeg’s sword which pushes down on the weave to tighten it is chance, Ishmael says. This is a rich subject for young people to consider as they begin to develop true freedom. How do people gain freedom in a web of necessity, fate and chance? Perhaps the most interesting and most elusive symbol is the white whale: A body of colorless void? An uncontrollable urge? Melville mentions that within the ocean is “the ungraspable phantom of life.” Is that it? What is it?! If you remember, becoming aware of the existence of forces one can’t understand or control is the mark of adolescence; it is what filled us with feeling and got us thinking.

“My experience of teaching Moby Dick to young people was that the students’ conversations were a journey into an uncharted sea.”

Lastly, Moby Dick is indeed a sophisticated read. Herman Melville’s language is elevating, and the students read it, speak it, learn it by heart, choose passages that they love, and begin to ingest it and make it all their own. Last time I taught the main lesson, we closed with a final conversation reflecting on the course where one student remarked that their own creative writing had improved during the main lesson. Another called from across the circle, “It’s the language; it’s because of the language [of Moby Dick].”

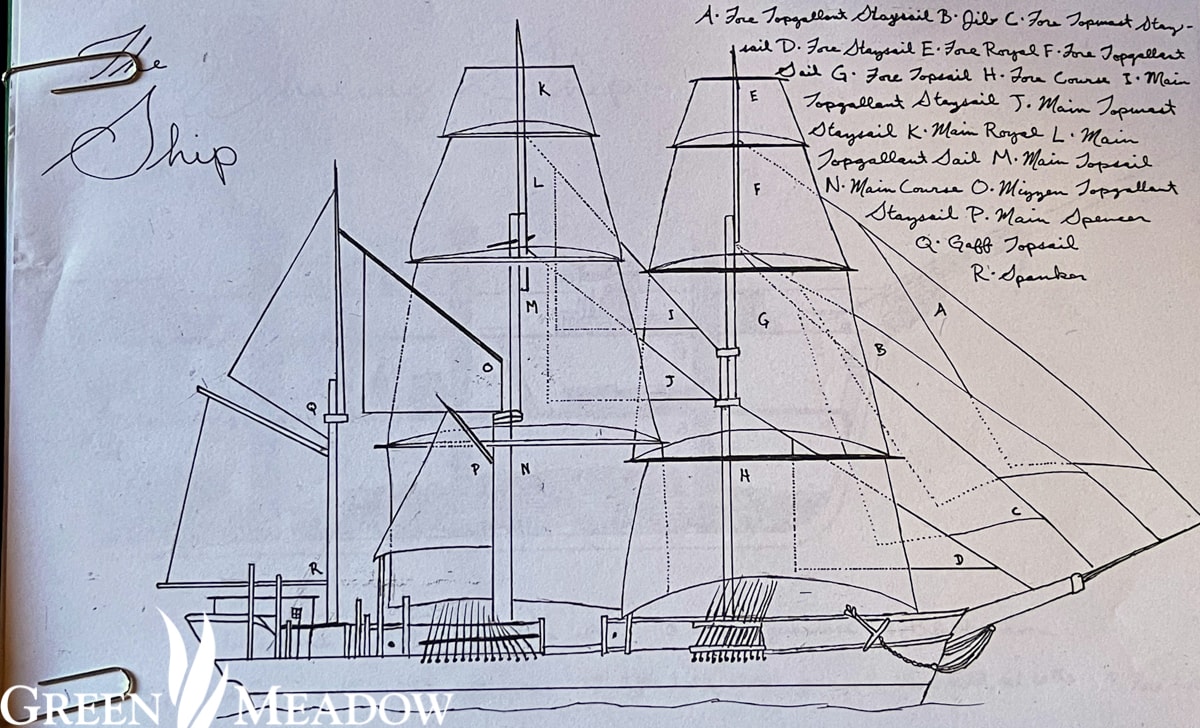

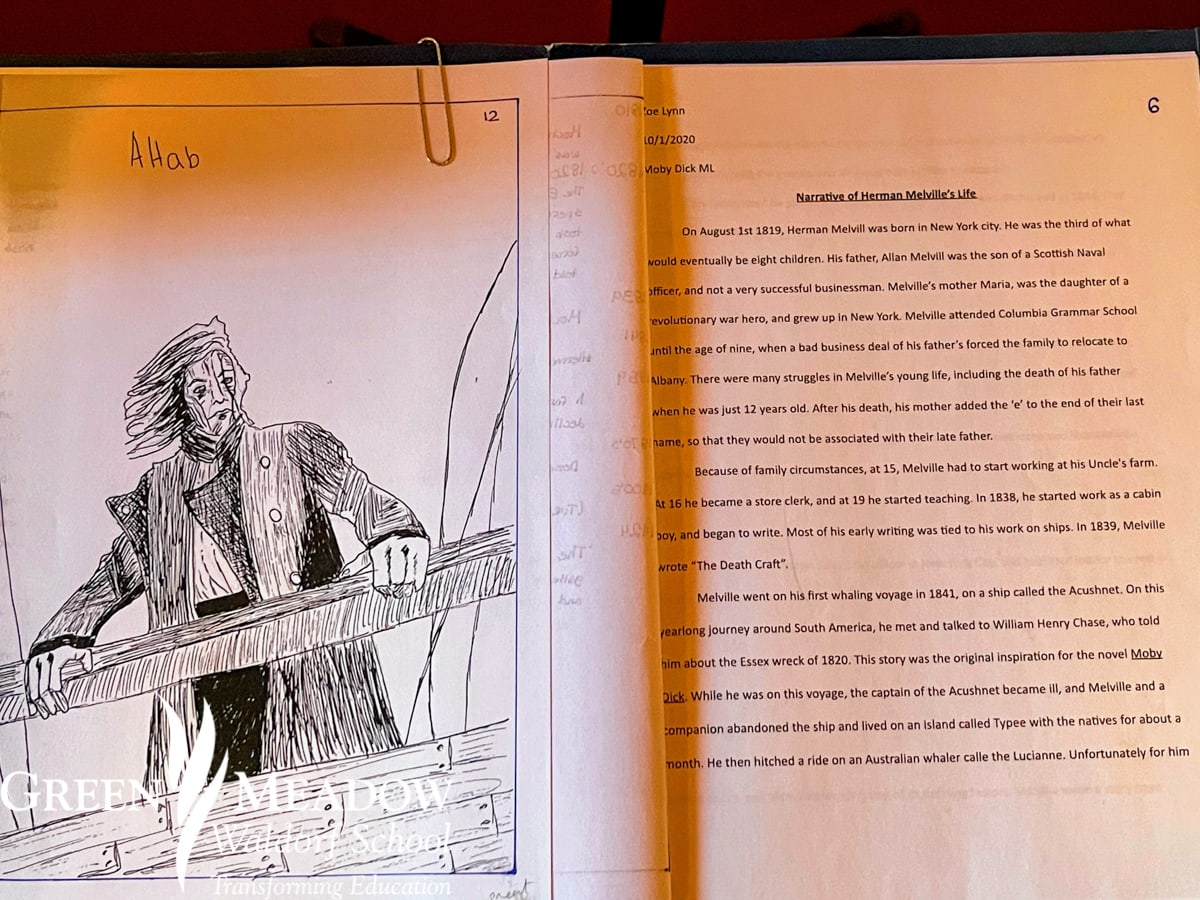

My experience of teaching Moby Dick to young people was that the students’ conversations were a journey into an uncharted sea. Their writing was a kind of charting of a path of thought and feeling. Their essays were marked by strong, objective observations, clear thinking, emotional commitment and beautiful language. I notice how much they also love more practical tasks like tying knots, naming the parts of the whaling ship, and tracking the path of the Pequod. When asked to work an independent project of their own, they have baked hard tac, fashioned lances and harpoons, painted images from the novel, composed songs and created short films. Looking back on their high school years, students will often cite the final two days of the course as one of their favorite memories. We spend them at Mystic Seaport where students have an opportunity to sleep on a ship, explore the W. Charles Morgan (the oldest surviving whaling vessel), climb rigging, row whale boats, throw harpoons, and speak to the world famous Melville scholar Mary K. Bercaw Edwards.

Friedrich Schiller: “Keep true to the dreams of thy youth.”

I don’t think our students would be surprised by Philbrick’s book. Once they study Melville’s epic novel, they will have touched upon Philbrick’s ideas themselves. I did find one detail in his book that I treasure and will hold in my mind as I savor this course with the ninth graders. According to Philbrick, after Melville died, his family found a piece of paper taped inside his writing desk inscribed with the words by Friedrich Schiller: “Keep true to the dreams of thy youth.”