By Harlan Gilbert, High School Math and Science Teacher

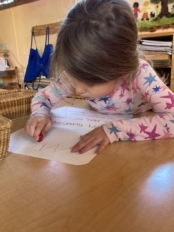

In the Kindergarten, children are active in wind, water, and soil conditions in every weather. These rich, holistic, practical experiences are not only joyous parts of childhood. They also give an unparalleled basis for comprehending the world in myriad ways. Upon this solid foundation of investigation into the natural world, scientific understanding can later build. At this age, the first ecological consciousness of the immediate environment forms through the children’s daily experiences of adults cultivating the natural world in healthy ways. One of the teachers’ primary goals is to model responsible citizenship in the natural world. Thus the importance given to garden work, tending the land by planting, watering and weeding in springtime, harvesting in summer, raking in autumn, shoveling snow in winter, and many more activities.

The curriculum of the first elementary school grades wisely includes extensive time for lessons on environmental awareness. In these years, students learn to “read the book of nature,” coming to recognize the wondrous range of animals and plants that live and land formations that form their surroundings. Imaginative descriptions form the basis of nature education at this age. For example, some years ago a First Grade teacher at Green Meadow named the low-lying area near the Arts Building the “Rocky Dell,” turning the area into an imaginative homeland for a generation of students, whose creative play has blossomed in this complex landscape.

Science lessons in these early grades center around stories of nature, bringing alive the wild and cultivated plants, the domesticated and wild animals, the streams and hills, the winds, and the stars, sun, and moon as intimately experienced aspects of our lives, just as the traditional stories of native peoples did for their children. After hearing a story about the mighty oak and the lithe willow, for example, students visit these in their natural setting. Ideally, the names and character of the elements of the natural world become a natural vocabulary for young children, so that by the time they are around nine years of age they should be able to recognize and name many of the local plants and animals, land formations, constellations of stars, etc., as naturally as they recognize and name each other.

In the following grades, the Waldorf curriculum leads students systematically further in their scientific understanding. This begins in Third Grade with an exploration of the ways humanity can take responsibility and care for the natural world of soil, plants, and animals. The Farming block in this year guides children to comprehend the farmer’s role as sustainer of the health of the Earth, balancing the interrelated needs of soil, crops, and livestock. They come to understand that healthy soil is the basis for healthy crops, that healthy crops are the basis for healthy livestock, and that healthy livestock and crops provide the manure and compost needed for healthy soil. The cycle is complete.

The Third Grade also includes a study of Building. Building depends upon understanding how the natural environment can be used to create stable structures, Understanding how different peoples developed unique architectural styles based upon the available materials illumines the natural environment from a new perspective. Building structures using at least one of these styles allows students to comprehend on a kinetic, tactile level the nature of materials and the principles of structure. As architecture advanced, building also came to depend upon the cooperation of a variety of people, each with special skills (masons, carpenters, glaziers, roofers, plumbers, electricians, etc.). Imagine if we each had to excavate, build a foundation, put up walls and a roof, insulate, glaze, plumb, and wire our houses! What would most houses look like if each was wholly built by its owner?! Thus building offers insight into the importance of the ecology of human interaction.

In Fourth Grade, students study animals. They quickly discover how each animal has a specialized form and particular way of life suitable for its particular environment. Comparing this to how human beings live—and recalling the many building styles they explored in Third Grade—they can discover that, while animals’ relationship to their surroundings is fixed, human beings can live in harmony with any environment. This flexibility is possible because we can both adapt our way of life and transform the environment. We rely on wisdom, where animals depend upon instinct.

In Fifth Grade, Waldorf students study plants. This usually begins with a broad survey of the simplest organisms—mushrooms, algae, and mosses—and proceeds through increasing complexity to arrive at the flowering plants. Each plant is suited to a particular soil and climate, so it is natural to study the climatic zones, and to see how these are affected by both latitude and elevation.

The study of plants offers a glimpse of the principles of sexual reproduction. This has wondrous consequences: the “offspring” of simpler plants, which use asexual reproduction, are exactly like their parents; however, through sexual reproduction, each organism is absolutely unique. This applies to them, too: each human child, too, is absolutely unique.

In Sixth Grade, the stones come into focus. These offer a fascinating plethora of form, texture, and color, all arising through three basic processes: intense heat (igneous rock), intense pressure (sedimentary rock), and a combination of both heat and pressure (metamorphic rock). Crystal formations are highly geometric, allowing connections to the study of geometry undertaken in this year.

Also in Sixth Grade, students systematically explore the senses that inform us about the world around us. They explore optical, tactile, thermal, and acoustic experiences, and seek to comprehend the laws that underlie these. What conditions give rise to a rainbow? (Try a prism to find out!) When is sound transmitted along a material? (Does it matter if this material is wood or string?) Is our experience of warmth and cold absolute or relative? (Compare your experience of a 50-degree day in November with that of the same temperature in June!)

Many Sixth Graders are beginning to experiment systematically on their own, building model airplanes, creating stop-frame animations using materials such as clay or Lego, or trying out chemical experiments such as a vinegar and baking soda rocket. Green Meadow has recently started a Science Club, open to Sixth Grade and up, which extends the range of experimentation available to middle school students.

This new interest in experimental method is met strongly in Seventh and Eighth Grades through practical studies in mechanics (Can you lift a dumpster? Pull yourself up into the air?), chemistry (slaking lime, analyzing the elements of a burning candle), and electricity and magnetism (building a telegraph and motor). They study human anatomy, examining a real skeleton and drawing the organs of the body, and physiology, exploring how the human body operates and how diet, sleep, and lifestyle choices affect their health.

I hope that the above has whetted your appetites! To explore the rich scientific and technological curriculum of the high school would go beyond the limits of this essay, but perhaps another day…

Astonishingly, pyrites naturally crystallize into the shapes of all five Platonic solids. The cube (below) and octahedron (above) are shown.